|

Before I became a programmer, I was trying my hand at a lot of areas of study. It's probably a more accurate thing to say that me becoming a programmer was an accident that happened thanks to all the things I wanted to learn up to actually becoming a software and web developer. I studied graphic design in high school before falling in love with music theory my senior year and decided to audition for a music school and barely made it in. I studied music composition with the goal of writing music for video games before I started regularly designing and prototyping games with a friend. I learned that I really enjoyed the entire game development process and chose to study video game design on my own after getting my music degree. I couldn't afford another degree, so it was more or less a bunch of one-off classes of a DIY degree that demonstrated my experience rather than proving my schooling. Stifled by student debt from my college degree however, I needed something to help pay that off and I used the programming knowledge I picked up developing games (and the referral of a friend) to land my first programming job.

Why do I mention any of this though? Well, I hope it shows that I have a deeply-held enjoyment of video games. I find them a fascinating medium capable of involving the audience in a way that other media can't effectively do. I also enjoy thinking of ways to fuse other interests with the video game medium. After all, game design often starts with a core idea and designing a space around that core. It's a part of why it's so easy for people to agree of categorizing games in genres and how new games take core gameplay from a genre, adding a personal twist or something novel with hopes of that novel thing to become a staple in the genre going forward. It's a neat cycle that brings us to where video games are today. But I digress. Games that take one of my interests and see what they can do with it in a game setting really stand out to me. It's probably a big proponent of why I like rhythm games so much having spent a solid chunk of my educational career studying music, and percussion in particular. And if it isn't abundantly clear from writing for Prismatic Planet for almost 2 years now, ecology and the connectedness of nature is something I'm very interested in. I thought it'd be neat to find a game that attempts to virtualize how our planet works, and find one of those games I did! The game is called Equilinox, and I'd like to explore a bit about how this game attempts to replicate the natural world and its interactions with the species that make up its ecosystems. After all, it's a very human thing to have a fully functioning natural world right outside your door, but choose to make a digital one that you can influence and observe. Let's dive in!

0 Comments

This past Wednesday marked the autumnal equinox for 2021 where I'm situated. For those reading who might not be familiar with an equinox, it's considered a day in the year when day and night are very near equal. This usually amounts to the day when a location experiences close to an even split of 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of night. What makes it "autumnal" is that it happens in the season of Autumn (or Fall dependent on how you grew up learning about seasons). Despite this day not being a great indicator of an area's local climate, per se, it is generally observed as the "first day of autumn."

I have a certain fondness for fall. There's a warmth the word carries in contrast to the cooler temperatures that the season invites. Or at least that's how I've typically experienced the concept. It's the time of the year I'll start swapping out readily accessible shorts for readily accessible flannel pants. Short sleeves for long sleeves. Fireplaces become a actively used amenity where people have them, carrying a scent of wood through open chimneys into the air. And just about every food and drink shop breaks out the cinnamon, a notably "warm-flavored" spice in my book. Of course, there's no reason these sensations have to be locked to autumn. Well, maybe you wouldn't opt for long-sleeves in summer, but fireplaces and cinnamon don't have to lose their flair in the winter, yet somehow they do. I could approach this from a branding cynicism where local shops want to entice you with new seasonal items, and the more they change with the seasons, the more opportunities they have to present you a novel experience for the year. There's certainly truth in that, but seasons weren't built for the human capitalist machine. No, that machine merely adopted seasonality. But did humans adopt them too? Are seasons an invention or a discovery of humanity? Let's dive in!

When I was a kid, I loved to think about how things work. I distinctly recall being at book fairs and being unequivocally drawn to books about systems. In a way, the kinds of things I learn and write about here would probably have made child me very proud. I'd ask for books about how weather works, why volcanoes erupt, what causes earthquakes, and how to measure rainfall and wind speed. I, for whatever reason, really wanted to know how the world functioned, and enjoyed trying to understand some of the most complex topics I could get my hands on.

What's interesting about that mindset for kid me, though, is that I'd often learn what I wanted to learn and get immediately interested in the next question I could think to ask myself. Which, honestly, isn't all that surprising thinking that I wanted to learn all this stuff as a kid. It's like wanting the new shiny toy, but what I wanted was new shiny knowledge. The result is that I built up a lot a shallow knowledge about how things worked, effectively making myself a bit of a walking encyclopedia. It was fun to demonstrate that to people, but I found that I was essentially learning a ton of stuff, but never really applying it to anything. Little did I know, this was the beginning of a narrative for my life up until now. One that guided how I liked to learn things and shaped my view of the world. I'd say I'm at the end of my story, but I'm certain my thinking will continue to evolve as time goes on. It always does. But I wanted to share this trajectory with you. After all, I have a feeling my thinking is not unique, and you might see yourself at various points of this journey yourself. So, let's dive in!

Quick disclaimer that this post is more candidly thoughtful than most here. The thoughts within are more inquisitive based on the intersection of the human food system and nature rather than an analytical deep dive. I had been thinking about how "ugly food" services factor into that system and this is an attempt to stitch together a big picture from tangential, interconnected thoughts.

Hope you enjoy it!

Imagine yourself walking through your local grocery store. You're looking for some fruits and vegetables to bring home for a week's worth of meals and you're confronted with a plethora of delightful options. Yet, despite the brilliant display of colors and plenty before you, you're probably still going to pick up and put down at least a few of them before putting anything in your basket. There's this feeling while you're picking your groceries that out of these options, there is some perfect pick for you in the moment.

And, hey, maybe this is true. Maybe you're planning on making a fruit salad in a few days and you don't want the ripest fruit in the batch. It's going to be sitting on your countertop for a few days, and you'd like to account for that. Beyond that bit of planning, though, what is it that's making us be so selective about the food on display. It all looks good enough to prepare meals and cook with. Why are we doing this? You might be thinking that this is an instinctual human behavior, ensuring we're finding the food that's best for us. This is a correct thought. Humans, as with all animals, do need to go through a certain trial and error when being introduced to an environment. Before we knew which food to display, we needed to know which foods we could actually eat. To some extent, this selection behavior could be a residual habit of our ancestral gathering selves. But, in this environment, it's not about whether the food is edible. Beyond that ripeness point, our selection is one primarily of luxury. We're looking for an "ideal" food. So where does this concept come from? Let's dive in!

Over the course of the past year, a number of people have found themselves needing to work remotely for the first time in their lives. This kind of change can be jarring to anybody, especially when it happens so suddenly. On top of not having everything you're used to having while at work, you have to deal with a plethora of new details that were never present while at the office. Things like the distractions from children learning remotely and dealing with the noise of neighbors if you're living with a community of people. Things like finding that balance of when to step away from work when the home is your office. And, of course, having to keep in communication with colleagues through primarily digital means.

One aspect that I've found a surprising number of people talk about, however is less of a new obstacle and more of a new benefit: being more readily near a natural environment. When most of us think of our home, we aren't thinking about our closed off rooms with grid-system ceiling tiles and white fluorescent lighting. We typically surround ourselves in windows letting in the natural light and we're often just a few steps from the outdoors. To that extent, a not insignificant number of people found themselves engaging with their natural surroundings more often. Myself included! I'd like to take a look at this aspect of having worked remotely, of being closer to the outdoors. While statistics I mention throughout this post are from scientific studies and analysis of those studies, a lot of this will be my own experience, so bear that in mind as we press onward. With that said, let's dive in!

I started volunteering with my local arboretum over 2 years ago after wanting to take a more active role in my understanding of our home. I won't reminisce about this since I've done that at length in my first Human Nature blog post, but this volunteering was also my first foray into environmental stewardship. That is to say, the kind of volunteering I was doing (and still do) revolved around learning about plants and animals so I can actively participate in caring for the environment. This involves work like seed collection, seed propagation, monitoring, and aggressive species removal.

In my case, I have an intrinsic motivation to understand the environment around me. I like knowing about plants and animals that I see because it makes me feel more like a part of this world rather than an observer. Knowing what something is, when it's active, and what it can be used for is a fun skill to have and work on. While my immediate friends and family aren't as interested in the topic as me, it does occasionally provide some insight or a fun fact for them to take with them. Though, arguably, knowing what something is used for isn't actively helpful to me in modern life. I will not likely need to know medicinal or crafting properties of plants to make it through my life because I can depend on a society of people where someone else is using that knowledge to make things for me. What is helpful, however, is looking past the individual value of something and knowing how it interacts with other plants and animals in its local environment. These properties of life are still important, in my opinion, for everyone to have some knowledge of. If we see that an environment degrades so much that an entire species is suddenly gone, knowing how that species fit into the system lets us know what will be impacted next and how that could impact the larger system. When enough of these larger systems ripple into each other, they eventually hit humanity, so having a base knowledge of this interconnectedness keeps us, at a minimum, aware of when things are going to change and why. It's here that I find value in my environmental stewardship. I build an appreciation for the complex connectivity of everything on Earth. I'll never know it all, but by actively working to maintain and restore natural areas, I get to learn about my local community. Not just the human one, but the one of all living and non-living things. Let's dive in.

Earth Day 2021 was celebrated across the world this past Thursday, bringing people from all backgrounds together in an effort to further humanity's efforts of caring and advocating for our home. After doing research on the origins of Earth Day and other days like it last year, I learned that every Earth Day has a theme. These can be all sorts of things ranging from "Green Cities" rallying behind greenifying urban areas to "Protect Our Species" raising awareness for the rising level of extinctions that are happening around the globe. These themes help convey a unifying message spanning our actions around caring for the planet and can help people get behind a cause.

This unifying nature of the theme is a particularly human thing. Since the founding of Earth Day, it's been pretty clear that the goal of the day is to raise awareness on environmental issues and encourage others to care about our home. Yet every year we have a new theme focusing on some aspect of this broad goal. There is something inherently attractive to people being able to rally behind specific causes, which is why this kind of messaging is potent for us humans. Finding the right words to encourage participation in something is uniquely human. Given the Earth Day theme is a way to rally people behind environmental causes, I want to take a look at them to see if they succeed in conveying their underlying goal. With that on the table, this year's theme is "Restore Our Earth." Let's dive in!

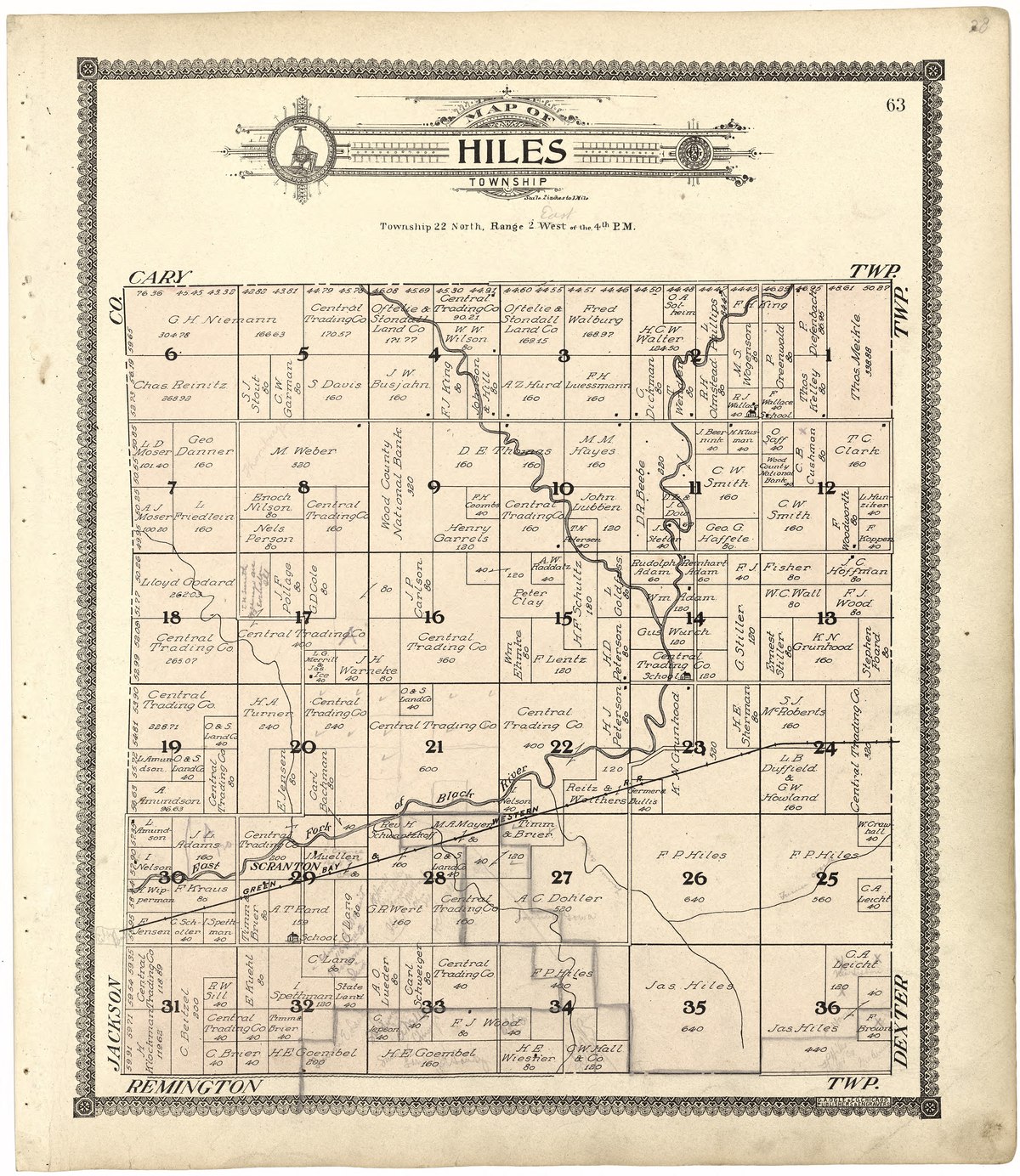

We had a particularly cold blast in February this year which made it too cold to get outdoors to volunteer at the arboretum. In its place, we had a Zoom session with volunteers who found the time to talk with each other. One of our stewards (essentially a leader for us volunteers) ended up sharing some research that he had been doing lately digging up old survey records from over a century past around the arboretum grounds.

It was pretty neat seeing some of the odd measurements that were used by the surveyors. And, yes, I did say odd and not old. While they are kind of both, I feel that odd best describes them. The meticulous nature I pictured of these groups of people working together to lay measuring chains across this country before western expansion of the United States happened was an odd one indeed. It made me want to learn more about these measurements, why they were being made, and how that influenced the shape of the country today. After all, the United States is a surprisingly consistent grid system east to west and this measuring seemed like it could be why. I ended up doing a little research of my own and wanted to share a bit about what I'd found, so let's dive in!

It's safe to say that humans are a powerful force on the Earth. We've stretched our influence far and wide, both in our own social structures and the physical ones we've built atop the natural world. It can be difficult to remember that we're a part of this massive planetary balancing act of systems since we seemingly bend them to our will, but it would be ill-conceived to think of that influence as control.

Beyond that influence, I was reminded this month of a bias humanity has. We tend to like the concept of an "untouched" nature. Not untouched by anything though, but humans in particular. Going even further, we're biased toward an appreciation of nature not touched by the people who brought modern civilization. It's easiest to think of these people as the European colonizers. If they or their descendants haven't touched it, it's considered untouched by humans. Along with this bias comes another more dangerous one however. When we categorize nature by its proximity to humans, deciding that nature adjacent to humanity is lesser nature, we have a tendency to take less care of it. We opt to care more about "true nature" far from home. We can think that's the nature worth saving, worth protecting. Yet, by ignoring our neighboring ecosystems, we have a slow but steady impact on nature far away. Let's explore this together.

Close your eyes and imagine yourself in a garden. What do you see?

Are you surrounded by towering trees, light peering through the canopy as shadows of leaves dance at your feet? Are you under a solitary sycamore, grasses swaying in the breeze as clouds race overhead? Perhaps you are upon a porch overlooking a vast collection of flowers on a light rainy day. Are you sitting, head level with your surroundings? Maybe you're standing to see as far as you possibly can. Or perhaps you're lying on your back, viewing the world from the perspective of the plants themselves. But most importantly, how do you feel? Humans have quite a history with gardens and how they can act as a connection to the world around them. How a garden makes one feel is an integral part of why people take the time to work and maintain these spaces. While reading, I found that even though humanity's collective approach to gardening does change with time and culture, there is an underlying theme to our desire to garden. Let's take a little journey together and rediscover the garden. |

AuthorPrismatic Planet wants to get excited for the planet, raise awareness of its inhabitants, and get smarter about Earth. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed