|

We had a particularly cold blast in February this year which made it too cold to get outdoors to volunteer at the arboretum. In its place, we had a Zoom session with volunteers who found the time to talk with each other. One of our stewards (essentially a leader for us volunteers) ended up sharing some research that he had been doing lately digging up old survey records from over a century past around the arboretum grounds.

It was pretty neat seeing some of the odd measurements that were used by the surveyors. And, yes, I did say odd and not old. While they are kind of both, I feel that odd best describes them. The meticulous nature I pictured of these groups of people working together to lay measuring chains across this country before western expansion of the United States happened was an odd one indeed. It made me want to learn more about these measurements, why they were being made, and how that influenced the shape of the country today. After all, the United States is a surprisingly consistent grid system east to west and this measuring seemed like it could be why. I ended up doing a little research of my own and wanted to share a bit about what I'd found, so let's dive in! Measuring Math

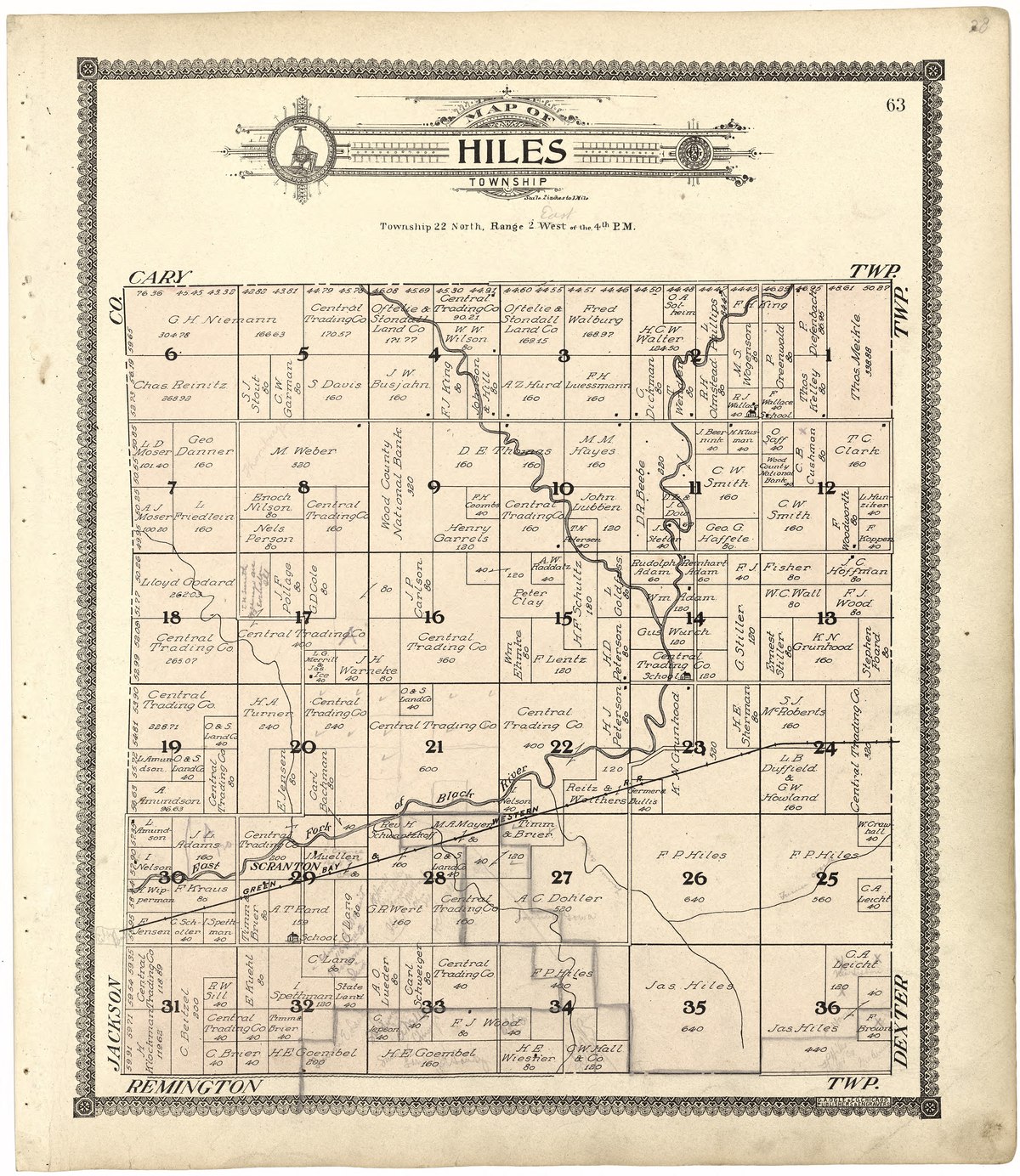

In that Zoom session I mentioned, we mostly talked about what the notes of the surveyors said rather than the means by which they were measuring out the land. We did go over that the tool used was called a Gunter's Chain, which is really quite peculiar, at least by today's standards. The chain is 66 feet long and split into 100 links. Each of these links is 7.92 inches long. Some of these chains also had loops on either end so the surveyors knew where to plant a stake in the ground as well.

Now, 66 feet seems like a strange number to be measuring with, but where the math magic comes into play is in the number of times this length is repeated. The US government tasked the surveyors with plotting out 36 square mile sections called "survey townships." That's still a bit of a leap in logic though, so let's add some of these chains together. 10 of these chains equal what is called a furlong. For any farmers or agricultural aficionados reading this, the connection might already be clear. But for those like myself who don't recognize that term, a furlong used to measured as the length an ox could plow without rest. Standardizing on that term these days, a furlong is one eighth of a mile. So we're making some progress here! 10 chains is a furlong, and 8 furlongs is a mile. 36 of these 80-chain lengths is one side of a survey township! So that's great and all, but why choose these super weird numbers and divisions to begin with? A System Steeped in Money

This is where we get into the motive for the measuring in the first place. Prior to this survey being underway, the United States had just come out of its revolutionary war. It was in a fair bit of debt and was looking for ways to repay it. The leaders at the time knew that there was a great deal of land to the west and if they could encourage people to buy this land, they could use that money to repay their debts.

They also knew people wouldn't want to just randomly claim a stake in unknown territory. At this time, it was considered that a 40-acre patch of land was enough to make a living on as a farmer, and this is why the 36-mile survey township was decided on. But we didn't measure the land in acres before, we measured it in chains, furlongs, and miles. How does that math play out? 36 square miles is 640 acres. If we quarter that area, we get 4 160-acre squares. And if we quarter those quarters, we get squares of...you guessed it...40 acres! These patches of land were split up in these interesting ways to sell from the start. And this segmenting of the measured land was used not only to sell to the "normal" folk wanting to travel west, but just as well to larger groups and states wanting to build on the land too. Frontiersmen, railroad tycoons, and university builders all bought their land in these 40-acre chunks made possible by the surveyors. The Myth of the Wild Frontier

This is more of an aside than a section, but I thought this was kind of a neat point. When I was growing up, the way the western expansion tale was told always made me think of these groups of people caravaning into the unknown to lay down a stake in a mysterious place they hadn't seen before. And while there is some truth in that last part, learning about the role of the surveyors here kind of diminishes that fantasy a bit.

Think about it. It wasn't these nomadic cowboys pressing further west in uncharted territory looking for a place to call home. They literally bought the square off the shelf. They knew exactly where to go to build their home. I, by no means, think this wasn't a difficult journey. I can't imagine moving my home and family by caravan across the country, but this is considerably less wild than old stories made me believe. I don't think I'm alone in not knowing about how there surveyors were really the frontiersmen in US history, though. Most reading I was doing on the topic usually noted these groups as unsung contributors to how the country even managed to spread west to begin with. Their journals often told of the swaths of swamps, forests, and prairies they waded through to make these measurements so others could travel more easily in the future. So, I suppose this isn't so much a myth of the wild frontier as much as it is that the people who did most of the discovering of the environment wasn't the people moving west, but the people studying the environment for the government to eventually sell. A Problematic Ulterior Motive

Knowing where the United States sits now, I can't say it's terribly surprising to see that its past is particularly driven by financial gain. While this motive isn't, in and of itself, problematic (repaying allies in conflict isn't a bad thing), having a money-driven motive can have its downsides. I say can, but in this case it most certainly had its downsides.

Starting with the less egregious of the major problems here, we have motive at conflict with what was intended to be documented. The surveyors that mapped the United States were not really out there to take a full inventory on the environment, just to sanction it into sell-able squares on a marketplace. As such, we did learn a fair bit about the perimeters of these areas, and that did lead to a good understanding of a good chunk of the environment spanning the United States, but there were glaring holes in surveyor observations due to the nature of the task. In that Zoom session from the beginning of this post, we read over the surveyors' notes of the area and it did, in quite some detail, describe the area around where the chains were laid. However, parts of what are now the arboretum which have been there this entire time were not accurately documented for decades to come. The initial survey didn't value learning about the environment for knowledge's sake. As long as the squares were documented and notes about the perimeter could assess the value of the whole, the interior of these areas were largely left to assumption until people came to live there. It's a little sad to know that so much more could have been known if not for the expedited nature of wanting to sell the land rather than learn about it. The other, much more egregious, issue is what this did to the indigenous people of the United States. This land was considered by the US leaders to be theirs by right and all they had to do was stake it out. This is about the time that the concept of "manifest destiny" started floating about to validate the effective stealing and pillaging of environments other human beings had come to call home. That this land had value in the eyes of US leadership, the people on that land were merely an obstacle to be overcome. If I thought that simply not documenting the entirety of the environment the United States sits upon was discouraging, the amount of inherent, unwritten knowledge lost in the oral traditions of North America's indigenous peoples is, in no uncertain terms, a tragedy. I say this because the step ahead of surveying was always taking the land first and forcing its inhabitants out. By any means necessary in the view of the United States at that time. In both of these cases, we see a bit of a double-edged sword here. We did, in the worst way possible, learn a lot about the environment of the United States by surveying the land. Due to a need to sell this land, however, "a lot" is a far cry from what we could have learned in its place. These days, we have a better idea of a socially equitable approach to learning about the environment in the United States. Likely in large part to a ton of damage already being done, but being able to look back at how the US operated in the past should give us an example of what never to do again and continue on a path that values understanding the planet on that merit alone, not one of exploitative gain. It's digging into stories like these that can be the most enlightening. From my perspective, my history books rarely shined a light on how the United States' story unfolded. Often leaving out massive details to leave a story that makes the humans of the time seem amazing. But there's a lot there that goes unsaid, from the surveyors that gave us the baseline knowledge of the environment in the US we continue to build on today to the tragic reality of how much we actually lost in pursuit of that goal for greed. Not to undermine that note, though, we do have to realize that the past is something to learn from and not to dwell on and give up. Humans can and should be able to improve themselves over time, and we certainly have the resolve to do just that. We need to recognize the knowledge we have today always comes at some historic cost, and we should always strive for a more equitable way forward knowing where we came from and just how much we have to gain by taking those much needed steps away from past behavior.

~ And, as always, don't forget to keep wondering ~

Resources:

Measurement Details https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gunter%27s_chain History https://www.americanheritage.com/measurement-built-america#1

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPrismatic Planet wants to get excited for the planet, raise awareness of its inhabitants, and get smarter about Earth. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed